2nd January, 1849

This morning, I was awoken most suddenly—quite before the hour—by a dreadful, piercing cry, such as I have never before heard. At first, I thought myself trapped in some nightmare, for the sound was like that of an infant in the most terrible distress—shrill, ragged, utterly inconsolable. My heart quickened at once. I sat upright, the air bitter against my skin, and then came another noise—commotion, raised voices, perhaps out in the street?

I rushed to the window, fumbling with the latch in the half-light, and there—oh, God help me—there she lay. A girl. Collapsed in the road. Motionless. And the child—the child was wailing still. My hands began to shake.

I scarcely recall how I dressed—my nightdress, robe, and slippers, nothing more—but I remember how cold the banister felt beneath my fingers as I descended. My legs were trembling most shamefully.

In the hall, I found the servants abuzz—Griffiths speaking low to the footman, and the maids pressed like gawping ghouls to the drawing room window. Griffiths turned as I came down and bid me, quite firmly, to go back to bed. “It is no concern of yours, sir,” he said, “just some ragged girl from the slums.”

But I could not. I would not. I told him quite breathlessly to stand aside. “There is a girl out there,” I said—my voice cracked—“and a babe in her arms. Are we to let them perish?”

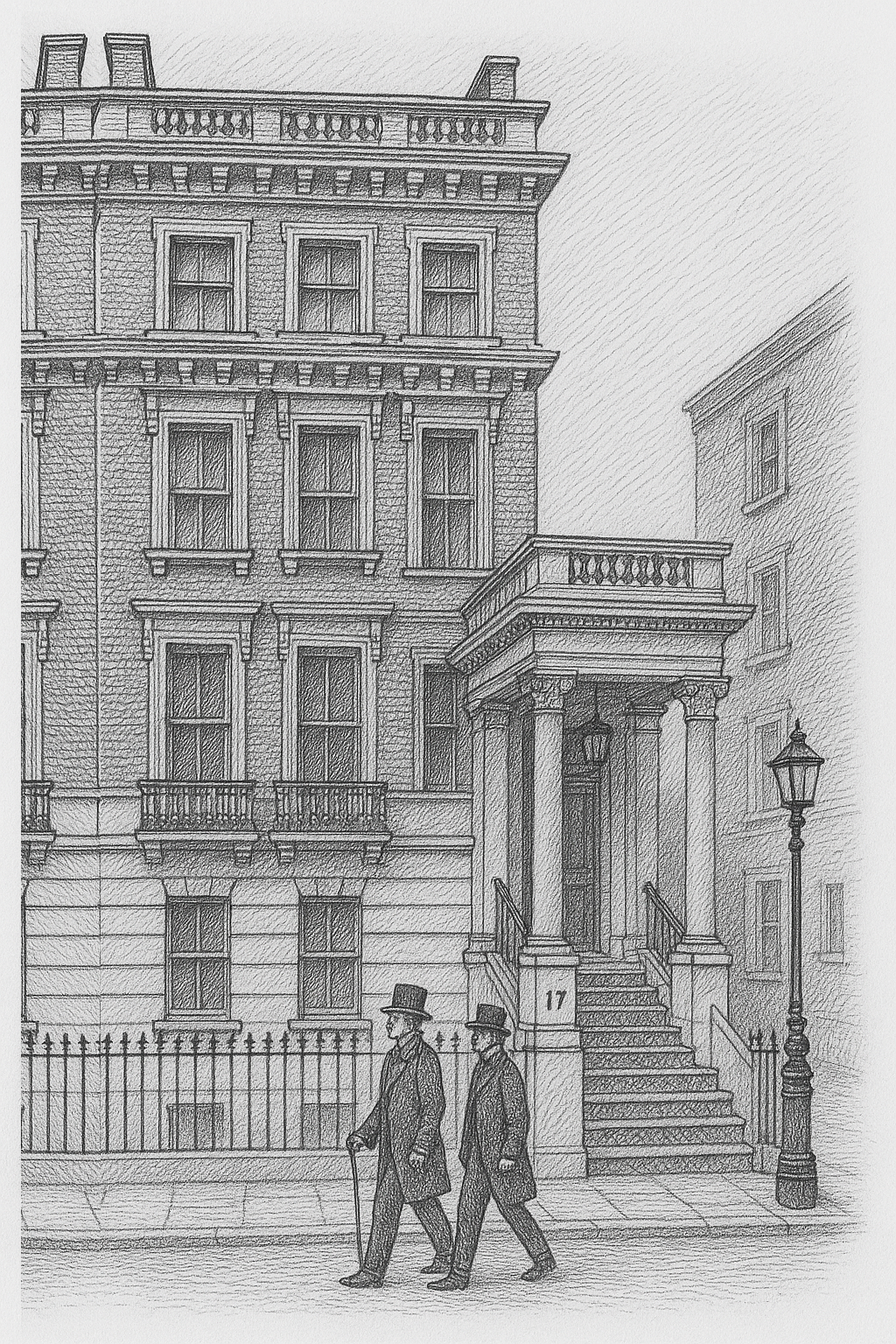

Outside, the cold bit at me. I stepped out onto the stoop, and the sight that met me quite near took the strength from my knees. The girl in the road—dear God—was Florence.

She was barely conscious, her limbs curled as if drawn by some final reflex, and wrapped tight to her chest, the babe, screaming, his tiny fists like knots of blue. For a moment I stood, frozen by the sight, unable to move or think. I felt so very unsure of myself. I wished someone—anyone—might step forward and tell me what to do.

But there was only me. And so, I swallowed down the rising panic and called for Griffiths and the footman. I dared not touch Florence, not then, though every inch of me ached to. Instead, I bent to the child. I undid the shawl about her chest—my fingers clumsy—and lifted the infant as carefully as I could. He was so light. So cold.

The neighbours across the road stared. One woman gasped aloud, no doubt scandalised by the sight of me in my robe. I felt my cheeks burn, but I would not retreat. Griffiths and the footman came, at last, and I instructed them—oh, so earnestly—to be gentle. “Do not jostle her,” I begged. “She is hurt. She must be.”

Back inside, I sent Maude to fetch Dr. Ellison. She went most reluctantly, I must say, muttering as she departed.